If you have spent anytime outdoors in the Central Maine area in the past three months you have likely become well acquainted with the brown-tail moth. Since late April they have covered almost every outdoor surface, leaving Mainers suffering from terrible rash.

There is nothing like having to mow or weed whack your lawn in a full body suit in June out of fear that you might soon become covered in thousands of toxic hairs. For those of us that commit to living in Maine full time, the last thing you want to do is sacrifice one of those precious five months where you are almost guaranteed to not see snowfall.

Brown-tail Moth Dorsal Side

Brown-tail Moth Dorsal Side

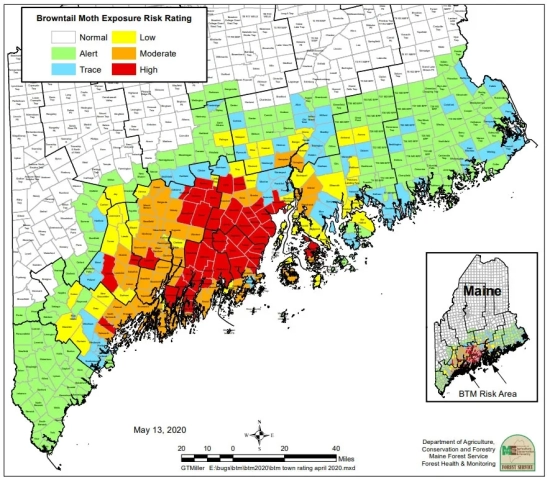

So where did they come from? Brown-tail moth was initially introduced to Somerville Massachusetts in 1897. They quickly spread to all New England states by 1913, at the time of introduction populations of moths were very high, slowly dwindling through natural controls until they were limited to a small population in Cape Cod in 1960. Like many moth species, both native and introduced, brown-tail moths are subject to "boom and bust" population cycles. At the time being it may seem like this infestation is hopeless and without end, but nature demands balance. Over the course of a couple of years, caterpillars and moths will be subjected to limiting factors in their population. With population increase comes lack of food, disease and predation. Upon initial introduction, invasive species are generally subjected to fewer limiting factors. Because they have not evolved within the ecosystem which they have been introduced, they have no natural predators. Over time, this imbalance has shown to reduce as native species learn to consume or compete with these new arrivals. Introduction of parasitoid wasp and fly species, as well as the use of species specific disease to mitigate their populations is being explored as a management technique (Aliens and Bodysnatchers, Beckwith). Ultimately, these little menaces will not go unchecked, but it may take some time.

Regardless, we continue to pour time and resources into management and research. While Maine is now home to countless invasive species, the brown-tail presents a unique risk to public health. While most exposures manifest exclusively as painful rashes, some individuals experience respiratory distress. When the potential of coming in contact with a caterpillar is impacting people's everyday activities, it's an issue that should be sounding the alarm. Where the species remains relatively isolated to the State of Maine, it is often difficult to convey the gravity of the situation to relief organizations outside of the state. Most large private and federal funding organizations often offer top priority to projects that can grant them the "most bang for their buck", or hot-topic issues that are relevant to a higher percentage of the countries population.

This hasn't stopped a handful of dedicated individuals and organizations from taking on the task. Dr. Angela Mech, Assistant Professor of Forest Entomology at the University of Maine is focused on developing an effective monitoring program for the brown-tail moth. You may have noticed traps hanging from trees in various locations at the Arboretum, they are traps set out by Mech's students in an attempt to determine the effectiveness of different trap designs. By developing an effective monitoring program we will be able to better predict outbreak years, allowing communities to better prepare themselves for the moths in the future.

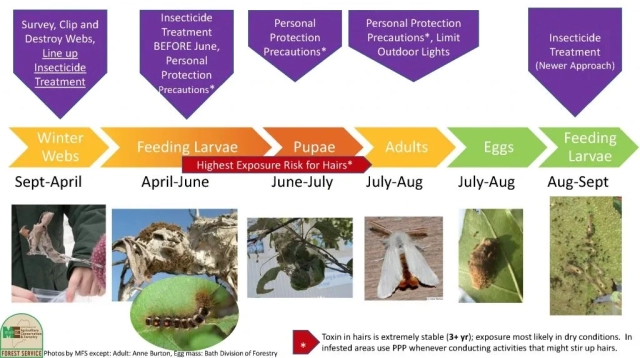

For now, we should be prepared to find a way to live with the brown-tail moth. Unfortunately, we have not seen the last of those very itchy caterpillars this year, a second wave is imminent in August and September. Moths are currently emerging from their pupae stage by the thousands, the ones you see fluttering beneath street lamps and attached to the sides of your buildings are largely males, as female moths are incapable of long-distance flights. Male moths will seek out females waiting in nearby trees, and together they will produce the subsequent generation of brown-tail moths. It is the larvae from this late season hatch that will over winter in their tree-top webs and produce next seasons infestation. In hopes of breaking the cycle you may be tempted to construct homemade traps by suspending a light fixture over a bucket of water, or installing bug-zappers - resist the urge! Studies have shown that leaving any outdoor light on, even those associated with a trap, resulted in higher populations of brown-tail moths in the surrounding area the following season. Management of this pest is most effective when individuals are in their larval or dormant stage.